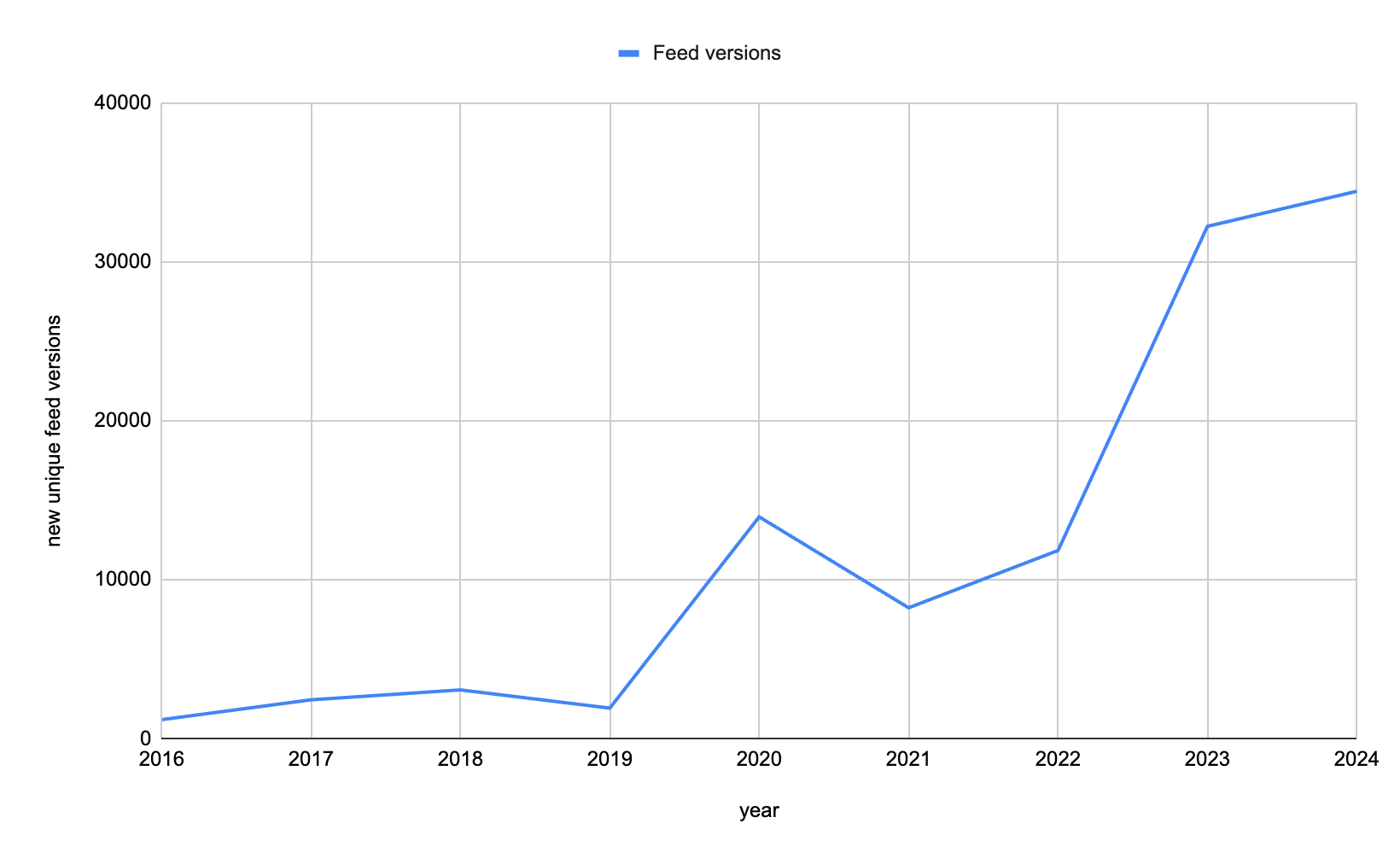

Transitland monitors schedule data for thousands of public transit operators. This data is collected and archived — currently at a pace of tens of thousands of updates per year:

We rely on operators to set their own policies for updates to their schedule data, and the time period covered by that schedule data. Operators may publish data that contains scheduled service for the next week, the next month, or even the next year. In some instances, operators publish data that only contains service that begins at a future date. This is a critical, and often hidden, factor in how useful the data is to riders and other data consumers.

The "7-day rule"

Data that changes frequently or data that only contains schedules for the next few days struggles against an important constraint: Data consumers might require many hours or days before data updates can be processed and available. (For example, to rebuild a routing graph used in trip-planning software.) These constraints mean service changes may be in effect, on the ground, before these changes can be communicated back to riders, via apps and websites.

Schedules that contain less than a week of future scheduled service can also force consumers to make (often faulty) assumptions about trips on future dates.

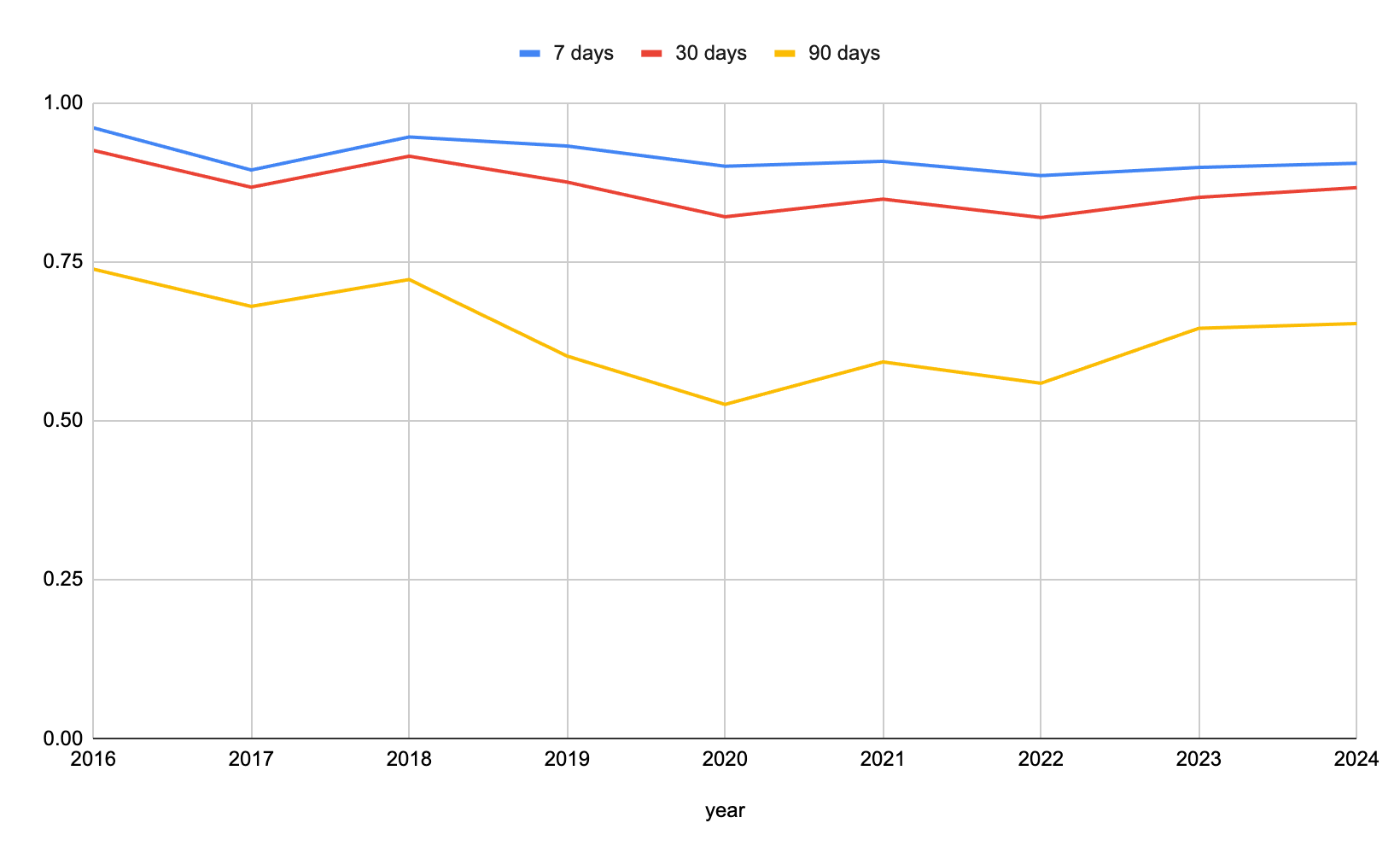

Currently, the GTFS Best Practices guide recommends publishing data for the current data plus at least 7 days in the future; we'll call this the "7-day rule."

Fortunately, this is a mostly "good news" situation.

Using Transitland's feed archive to assess update frequency

Averaged across all transit operators in Transitland, about 95% of static schedule updates follow the 7-day rule. This number remains about 90% even when expanding the future service window to 30 days.

It's also a good picture when disaggregating and looking at the individual operator level: The vast majority of operators have 100% of schedule updates following the 7-day rule.

The most common exceptions are:

- operators that have a tendency to publish data that begins in the future, with no scheduled service on the date of publication

- operators that fail to update the values in

feed_info.txtwhich explicitly set the range of valid service dates and remove guesswork and ambiguity for the data consumer.

Even if these exceptions apply to comparatively few feeds, it's still unfortunate if they occur in feeds that are important to a data consumer's use-case (e.g., to provide up-to-date trip-planning for travelers on an important transit operator).

Even more carefully characterizing updates

This provides an optimistic baseline for the current state of GTFS updates. For an even more holistic picture, we also need to incorporate a few additional metrics:

- Percentage of days for each operator where the data is "stale", that is, outside the scheduled service window for the last published data.

- The number of operators that publish data on a very frequent basis that assumes consumers have a fast turn-around process, and the characteristics of these updates.

These questions will be explored in a future blog post.